Editorial

Guillermo Vilas: The Number One That Never Was

UbiTennis has collected the words that journalists and reviewers around the world have written on the new Netflix documentary, “Guillermo Vilas: Settling the Score”, which depicts a 12-year-long campaign to have the ATP recognise the Argentine champion as a former world number one.

Published

4 years agoon

This article was originally published by “Lo Slalom”, an Italian newsletter

On rewriting history or just making it clearer, by Monica Platas, Mundo Deportivo

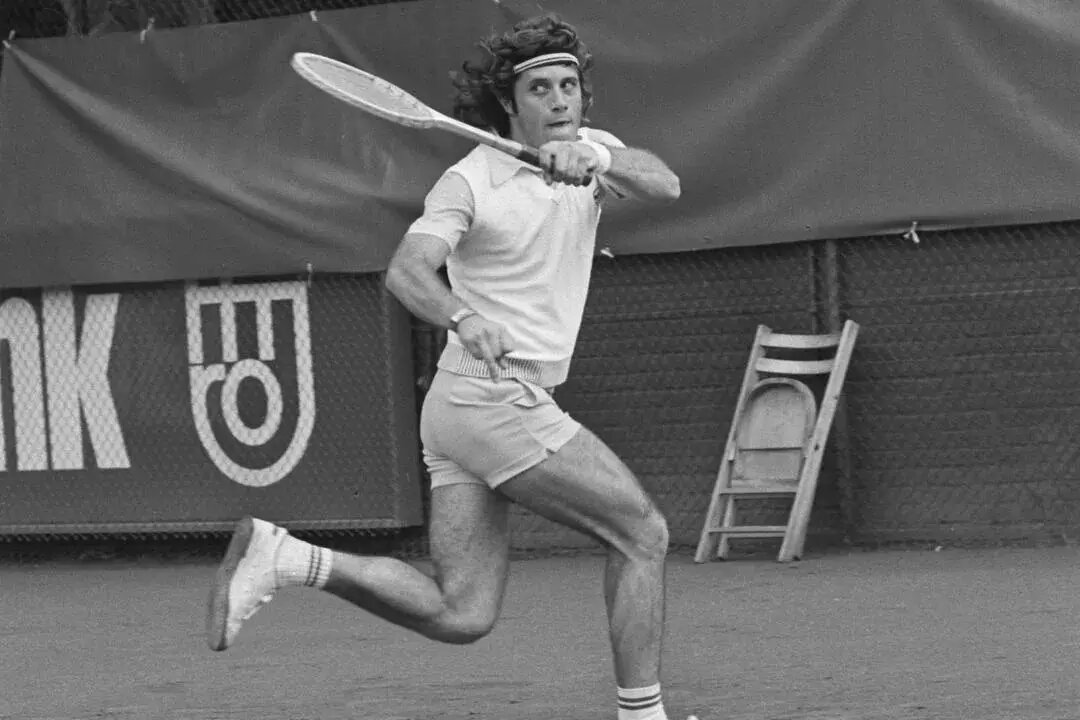

Now 68, during his tennis career the Argentinian won four Grand Slam tournaments. In particular, in 1977 he won the Roland Garros, the US Open and 14 more tournaments, for a career total of 62. He had a record 53-match winning streak on clay courts, a feat surpassed only by Nadal. Vilas climbed to the second spot in the world ranking on April 30, 1975, keeping it for 83 weeks, but he never reached the top.

Netflix has just released a documentary titled “Guillermo Vilas: Settling the Score”. It describes the statistical investigation of Argentine journalist Eduardo Puppo, who demonstrates how and why the ATP never recognised that Vilas should have been No. 1 in the ranking at least once during the best years of his career.

Vilas was famous for several things: his Southpaw shotmaking, amazing topspin, long hair, and bizarre behaviour. The newly founded Grand Prix circuit made use of very rudimentary technology in order to compute the players’ ranking, a system that painstakingly lacked rigor in its calculations. Because of this, the ATP does not recognise Vilas as a former number one to this day, but Eduardo Puppo has spent twelve years campaigning for the Argentine to be given what’s due. He produced a detailed report of 25,000 pages, recalculating the rankings in the period between August 1973 and the end of 1978. He finally demonstrated that Vilas did actually climb to the top of the rankings, outperforming Borg and Connors during some periods.

The Netflix documentary film shows the reporter’s frustrated illusion and emotional exhaustion facing this daunting task, but Puppo’s disappointment for the ATP’s repeated refusal to update the records is also central to the narrative. In an e-mail, the reporter is told: “Please don’t rewrite history.” This personal, professional and emotional journey on Puppo’s part is an effective narrative way to see again the biography of Guillermo Vilas in parallel with the Puppo’s work. In the documentary, we can listen to some fragments of the tape recordings that Vilas himself recorded while traveling around the world (these fragments were actually useless due to the low quality of the sound). The documentary film poses an interesting dilemma: since the aim of Puppo’s work is to recognize the merits of an athlete’s career, is this just an attempt to rewrite the history or is it a bona fide act of justice? The documentary includes statements by Federer, Becker, Nadal, Sabatini, Wilander and Borg honouring Guillermo by acknowledging his prominence in the sport. Neither Guillermo Vilas nor his journalist friend got the recognition they were looking for, but even if it’s not the same, the documentary will forever remain as a tribute. It does not help to rewrite the history of tennis, but it helps to explain it better.

A healed fracture by Furio Zara, Blog Overtime Festival

A man, an obsession, an injustice. A story of sports and life. This documentary is a little gem that helps to define clearly and with love the profile of a champion mocked by ill fate.

What a fabulous tennis player. Vilas is manly, intractable, but only for a just cause. Ambition’s fire burned inside him. He was the son of a lawyer, raised in the comfort of the Argentine middle class. A pure lefty, he wore a band in his hair like his frenemy Borg; an introverted man by nature, women loved him nevertheless. A poet on and off the court, he dedicated a composition to Caroline, Princess of Hanover. One of the best players on the dirt, he considered Wimbledon a court of “grass for cows.” Never to be tamed, he was capable of sensational strokes, a revolutionary who changed the history of tennis and was a role model for those who came after him. He is the father of the “Gran Willy”, also known as the tweener. His back to the net, he hit the ball in mid-air between his legs. He said: “The idea came to my mind while observing an ad with the Argentine tennis player Juan Carlos Harriott. He hit a ball under the legs of a horse, obviously not with the racket but with a polo mallet. It seemed fantastic and I mimicked it in my game.”

The documentary was helmed by Mexican director Matias Guilbert. It shows the fondness for Vilas of authentic tennis legends such as Bjorn Borg, Rafael Nadal, Roger Federer, Rod Laver and Gabriela Sabatini. Federer honours him by saying, “he had a great influence on the tennis players who came after him.” Nowadays, Vilas is a 68-year-old man, an aging “bandolero” from the Pampas. He is suffering due to a neurodegenerative disease – there are only few moments of mental clarity in his daily life. As the title suggests, the aim of the documentary was not just to create a tribute to an unforgettable champion, but also to finally make things right.

The gift of imperishable memory for a man who is losing his own by Marco Ciriello, Facebook

It is a hard sell to demonstrate that mistakes were made in the computing of the tennis rankings and that Guillermo Vilas was the best player in the world at some point in the mid-1970s. Journalist Eduardo Puppo has done it, analysing matches and figures, and spent years seeking the evidence to pay tribute to this champion and to get him the accomplishment he deserves. While Puppo was looking for data, points and therefore gestures, victories, cities, fields, tournaments, racquets, Vilas lost his memory. The Netflix documentary film, “Guillermo Vilas: Settling the Score”, describes this endeavour, with the tapes recorded by Vilas reminiscing on his life, and the charts by Puppo aa a sort of backdrop to his playing career. It is a great act of love: for tennis, truth, and justice. People that do not know who Vilas is will fall in love with him. They will appreciate him not only for his lefty shots or for the strength of his game at the net. They will think highly of him also for Hendrix, for his vision of the world and his way of life, for having shown that an Argentine and a Swede (Borg) can complement each other: “Your forehand sucks like my backhand, so we helped each other.” Those who already know and love him will find more reasons to hold him in such high regard.

How Vilas’s undefeated streak came to an end, by Gianni Clerici

An Austrian genius, Werner Fisher, invented a curious way of stringing racquets, and a Yankee philologist nicknamed them “Spaghetti Racquets”. The rotation of the ball was so impressive that an outraged Vilas withdrew from the final of the Aix-en-Provence tournament against Nastase, who played the previous match with the “Spaghetti”. This kind of racket was belatedly declared illegal, Vilas’s long streak already broken at this point.

Vilas’s tears, by Mariano Ryan, Clarín

Is it necessary that Guillermo Vilas be recognized for what he was on a tennis court, i.e. a number one, a position he already occupies in Argentinian sports lore? And is it really essential, in order to understand his prominence, that someone should review his files and grant him the status of world-best for a few weeks, when for a whole year he clearly paced all his opponents? Is the ATP compelled to listen to the truth uncovered by Puppo in the documentary in order to provide justice? It is very likely that everything will remain as it has been until now and that the campaign will never produce the results it set out to accomplish. Nevertheless, his titles and triumphs cannot be cancelled. The image of Vilas will never change in people’s memory. A champion on and off the court. A stubborn man who wanted to be the best at what he did, and he was the best, for sure. His tears at the end of the documentary will last.

The reason behind Guillermo’s tears, from La Naciòn

This touching moment has its own story to tell. It happened at the end of 2016, just before the best Argentine tennis player in history moved to Monte Carlo. Vilas and Puppo were having a conversation about a book in progress. During their meeting, the camera was accidentally left on, and in that moment Vilas’s emotional distress fully showed. He couldn’t bear what he considered an injustice that had lasted for many years. Puppo holds him in the scene, hugs him and even mentions something about a tattoo on Guillermo’s left arm honouring Alejandro, the little brother he barely knew. When they became aware of the existence of that accidental registration, Puppo, Vilas and an attorney, Adrián Sautu de la Riestra, agreed that it should be included in the documentary film, despite the personal nature of the moment.

Earthly justice comes first, by Carlos Navarro, Punto de Break

The ending of the documentary is a sudden gut-punch. It’s akin to a stratospheric fifth set, an exciting title won in stoppage time. These final moments are the perfect conclusion to a journey that starts with the first steps of a young Argentine on the pro tour who ends up carving a spot for himself on the Mount Olympus of tennis. I don’t know if this beautiful Netflix documentary film will change anything. Neither the number one assigned by Tennis World magazine nor years of research can probably do that. What I do know is that it has become a proof to how humble people can do extraordinary things, of how an Argentine journalist and a Romanian mathematician could change the history of an entire sport. Vilas will end up being what he should have been because his life is in its final stages and earthly justice must come before higher ones.

The fragile Titans, by Andrés Burgo, La Nación

Fame, idolatry and eternity. But what about that number one spot? What is it to be the best? Few times I have seen a Titan look as fragile as Guillermo Vilas does in Netflix’s thrilling documentary. When I say fragile, I’m not talking about his health (that’s a private matter), but rather because, despite almost half a century passing by, the old gladiator still wants that the ATP to rectify its rankings. He is a champion, and we believe we are the ones who need champions, although maybe it’s the other way around. We believe that a champion is invincible. The ATP is more hateful than FIFA. Thinking about Maradona, a colleague reminds me of how interviews with Diego always ended in the 90s. “What do you miss in your life?” the reporter asked. “Being more beloved by the people,” Diego replied.

Borg never learned how to pronounce his first name, by Christopher Clarey (New York Times), via Twitter

The ATP did not release rankings regularly in the years when Vilas would have been the world N.1. The old system was based on players’ average results and thus penalized workhorses like Vilas. What I know for sure is he had the best season of any man in 1977. You would need a heart of stone not to feel Vilas’s pain in this film. It was not his quest in many ways. It started without him being aware of it, but being recognized as No. 1 clearly matters deeply to him. This film is also a chance to see remarkable footage of the young Vilas: flowing hair, soulful disposition and legs of steel. The strokes look languid in comparison to what Nadal & Co. do today. The game has evolved and, in my opinion, improved. But Vilas and Borg were great athletes who could have been stars today. Fun fact from the documentary: he and Borg were close friends despite the fact that the latter apparently never learned how to pronounce Guillermo’s first name.

A negative review

“My life is a discovery. I always look for meaning in every circumstance. The first time I saw fire, I burned myself and it was magnificent. It was warm and appealing, and I thought, ‘What if I touch it? Maybe the heat will get inside me. This is how I discovered the world and how I got here.’” In this way, Guillermo Vilas introduces himself in the documentary film directed by Matías Gueilburt. It’s a film about the Argentine athlete who was one of the great protagonists of world tennis in the 70s and 80s. He began hitting obsessively the ball against a wall in the garage of his house when he was six years old. The only restriction set by his mother was that he could break only one lightbulb a day. He was a stubborn son who chose an ostensibly “unprofitable career” against his parents’ wishes, a would-be lawyer in a country where idols were boxers like Carlos Monzón, Formula 1 drivers like Carlos Reutemann, and footballers like Mario Kempes. The work flows in a very scholastic way in comparison with other two that could be defined more experimental and fascinating, like “John McEnroe. In the realm of perfection”, directed by Julien Faraut and “Subject to Review”, directed by Theo Anthony. The documentary sifts through stock footage, unpublished audio (46 different samples!) recorded by Vilas himself since 1973, as well as interviews with champions who weigh in on his value as a player and on the innovations he brought to the game.

The story suddenly switches gears (and not for the better) when the world rankings come into play. The title and the opening minutes of the documentary evoke the image of a lonely man going through his growth and consecration while pigeonholing the different turning points that change his destiny from an open to a one-way path. A path with a final destination – triumph. Then, the narrative changes. From the obsessions of the man from Buenos Aires, we move to the obsession of a journalist, Eduardo Puppo, who tries to carry on Vilas’s battle. He wants to demonstrate that in some periods (especially 1975 and 1977, the year when Vilas won over 50 matches in a row) Vilas was at the top of the world rankings, despite the ATP claiming otherwise. The wish to re-write history is the reason why the quality of the documentary dips. The darkness and the demons that stir both in the champion and in his unexpected supporter vanish from the narration, losing the audience and blowing out the fire that constituted its initial appeal. (by Mazzino Montinari, Il Manifesto)

Translated by Giuseppe Di Paola; edited by Tommaso Villa

You may like

ATP

Lorenzo Musetti And His Coach Silence Their Critics

Social media do not forgive those who lose and go through moments of crisis. Not even if they are just 22 years old. Many had even questioned Lorenzo’s indisputable talent.

Published

2 weeks agoon

12/07/2024

What a revenge guys. Lorenzo Musetti doesn’t say it, the tennis player who always plays too close to the tarpaulins at the back of the court and will never even achieve the results of Richard Gasquet, the tennis player whose movements are too wide for playing well away from his favorite red clay courts, the tennis player who has no fighting spirit, but fades away when things start going wrong and does not put up a fight to come back but gives up.

Simone Tartarini, the most criticized coach of the last two years, the one who is only a provincial tennis instructor, does not say it. The one who should understand his limits and understand the urgent need to be supported by a supercoach, otherwise the overrated Musetti will struggle to stay in the top 50 in the world.

I say it.

Well, considering that everyone can make mistakes, that no one is perfect, I really wish those hundreds of pundits, who even here on Ubitennis have made all these hard comments on Lorenzo Musetti and Simone Tartarini, had seen the whole match that Lorenzo played against Taylor Fritz, a player who has won Eastbourne three times and reached the quarterfinals for the second time at Wimbledon (the first time he also lost in 5 sets to Rafa Nadal) and whose worth on grass is much greater than his ATP ranking, No.12.

I am not saying, though still enthusiastic for having witnessed a 3-hour-and-27-minute display of extraordinary tennis unleashed on court 1 by Lorenzo, that Fritz played his best tennis with remarkable continuity. Indeed he missed many forehands (of 55 unforced errors I think at least 45 were forehands) and his percentage of first serves was low: even if the overall stat stands at 65%, there were times when he didn’t reach 45%. Yet, the variety of Lorenzo’s lavish repertoire made the difference. He would have made anyone lose his bearings and play badly… except perhaps Novak Djokovic whom Lorenzo will be facing in the semifinals today.

Just as there were many who exaggerated in belittling Lorenzo’s skills, now many people are popping up, eager to compare him to Roger Federer, because of his one-handed backhand, his delicacy in touching the ball, his mastery in alternating shots, from spinning baseline groundstrokes, to covered strokes hit close to the baseline, a sort of half volley, from razor-sliced balls which do not rise from the grass, to daring dropshots followed by cheeky lob volleys that land regularly on the line or nearby. A show within the show. Blessed are those who, like me, enjoyed it on court no. 1.

The truth lies in the middle. We are talking about a 22-year-old player, just like Federer was in 2003 when he won his first Wimbledon (but in 2001 the Swiss had already beaten a fellow called Sampras), who is not in the top 5 in the world or even in the top 10 or top 15.

It makes absolutely no sense to compare him – just because he has reached his first Grand Slam semifinal at Wimbledon – with Federer who is considered one of the greatest of all time.

Federer played 46 Grand Slam semifinals. On 20 occasions he went on to win the tournament, on 11 he lost in the final, 15 times he was halted in the semifinals. But at a certain moment he won 23 straight semifinals! An insane record.

It is evident that any comparison with someone like Lorenzo who has just reached his first semi-final is quite ridicoulous. Roger played until he was 37, so how can you compare him with a 22-year-old boy who has reached his first semi-final, and you have no idea what he can do in the future?

However, we can already say today that Lorenzo’s tennis, for its stylistic elegance is an anomalous, if not unique, tennis. Not only because he plays a one-handed backhand, and with that fairy hand of his he plays it flat, with topspin, sliced… Who else can deliver such goods? There is still Dimitrov, the former BabyFed, perhaps Shapovalov, and sooner or later someone else will come out, but that’s it.

Lorenzo is not only elegant, but also unpredictable, spectacular, a beauty to watch. Those who had paid 200 euros for a ticket on court 1 certainly did not regret it.

I can’t remember a fifth set played better by an Italian tennis player at Wimbledon than the one played yesterday by Musetti. Well, perhaps the one lost 6-4 by Nicola Pietrangeli with Rod Laver in the 1960 semifinal, but I saw it on a 21-inch TV and in black and white when I was 10 years old. If I were to look back on all my memories, there might be another fifth set worth mentioning, but it certainly wasn’t a quarterfinal.

And Musetti won in grand style. I was terribly worried at the beginning, because honestly when my friend Claudio Giua of Repubblica asked me for a prediction after Fritz had won the fourth set 6-3, I thought that Lorenzo would not be able to forget that he had led 0-40 on Fritz’s serve in the fifth game of that set (as well as missing a fourth break point). And so I gave him a thumbs down. Perhaps I did it out of a pinch of unconscious superstition.

Instead, Lorenzo played an excellent first game, closing it with two straight aces, the fourth and fifth of his match. And in the next game he snatched the break that paved the way for the most important victory of his career to date, “after the birth of my son the most beautiful and unforgettable moment of my life” he said. At least until he has also beaten Djokovic at Wimbledon… was the joke that was immediately sneaking amid insiders in the press conference room.

I have to be honest and report that Taylor Fritz could have held his following service game, had he not netted a comfortable forehand winner. That miss was such a shock that 4 points later he dropped his service. Then Lorenzo rushed off to a 9-point winning streak. In a flash he was leading 4-0. The match was practically over.

Fritz, who at the end of the fourth set had won two more points, 121 vs 119, crumbled down. And Musetti instead… was in Heaven. How wonderful! A third Italian in the semifinals at Wimbledon in 4 years after Berrettini in 2021, Sinner one year ago and Lorenzo now in 2024.

Why not equal Berrettini’s final… but Lorenzo has to do even better than Berrettini! That is, he has to beat Djokovic, the 7 times Wimbledon champion. But Djokovic has sailed through a very lucky draw in this tournament and has never been seriously “tested”. The first rounds, Kopriva, Fearnley were ridiculous. In the third Popyrin was a slightly more serious opponent… And in fact he also won a set and dragged Novak to a tiebreak in the fourth. Then it was a really disappointing Holger Rune who showed up in the round of sixteen. Finally a heartbroken injured de Minaur could not even step out on court.

Against Djokovic Musetti (1-5 head-to-head) has shown, more in the two five-set matches he lost at Roland Garros than when he won in Monte Carlo, that he has the right type of game to unsettle him.

DjokerNole will not concede as many unforced forehand errors as Fritz, but he is not the same Djokovic who has lifted 7 Wimbledon trophies. Besides, Lorenzo is someone who has always played well when he has nothing to lose. He will play on the legendary Centre Court for the first time, but considering how he performed at his debut on Court One, he could play another great match without being overwhelmed by emotion.

The strategy set up by Musetti and his coach on Wednesday was perfect. He was constantly aggressive, always trying to dictate. I think that even against Djokovic he will always try to take over the rallies, varying his schemes as much as possible, also playing dropshots that the Serbian – inevitably still concerned about the state of his knee – may not be so willing to run down. In short, I expect another great match of our “Muso”, won or lost.

I hope he will not be intimidated at the beginning by Djokovic, by the centre court, by the emotion of a first Slam semifinal. Because if he were to lose the first set, coming back against Djokovic would not be like coming back in his match with Fritz.

I also think that, with a large part of the public supporting him, Lorenzo just has to throw in some great points from the beginning to get boosted up. Djokovic knows this and, with his great experience, will be very careful not to give away any free points. At the beginning as at the end.

Because Lorenzo has shown, with the semifinal in Stuttgart, the final at Queen’s and even more with yesterday’s match with Fritz, that he feels wonderfully at ease on grass, where his slice backhand is a formidable weapon, both when defending and attacking, where his shots down the line could be as effective as Djokovic’s and provided that his forehands and dropshots work as smoothly as against Fritz. The American, who missed many forehands, instead played very well off his backhand for most of the match. Djokovic will not be able to play much better than that. Lorenzo was capable of firing back on Wednesday, why not today as well?

A tough enterprise awaits our Musetti, yet not impossible.

Translated by Kingsley Elliot Kaye

Comments

Roland Garros 2024: Has Crowd Noise Reached Boiling Point Or Is It Hyperbole?

Daniil Medvedev was one of the players who commented on the debate surrounding the Roland Garros crowd.

Published

2 months agoon

30/05/2024

Roland Garros has often been a place with energetic crowds that have been involved in plenty of controversial moments but has it reached boiling point this year?

The Roland Garros have been involved in lots of heated moments over the years whether it’s been finals involving Novak Djokovic, whether it’s been that epic Garbine Muguruza against Kristina Mladenovic clash or any Alize Cornet or Gael Monfils match.

The French crowd isn’t afraid to show its true feelings as it’s been one of the most passionate atmosphere’s in the world.

However there has been debate in the past as to whether the crowd has been bordering on the edge of being disrespectful.

That debate has boiled over at this year’s event as it all started when David Goffin claimed the crowd on Court 14 spat gum in his direction during his five set win over Giovanni Mpetshi Perricard.

Furthermore Iga Swiatek was pleading with the crowd in her on-court interview to remain silent during the point as they were seen shouting during a volley.

This kind of behaviour from the crowd as well as the retaliation from the players has seen tournament director Amelie Mauresmo see stricter rules being enforced by security and umpires on both sides.

So has this issue reached boiling point or is this an over exaggeration? Well here is what some of the players think.

Paula Badosa

“I think she (Swiatek) cannot complain, because I played Court 8 and 9 and you can hear everything. Like, I can hear Suzanne Lenglen, Philippe Chatrier, Court 6, 7 during the points.

“I think she’s very lucky she can play all the time on Philippe Chatrier and she’s okay with that. But I don’t mind. As I said, I played in small courts these days, and I was hearing so much noise. In that moment, I’m just so focused on myself and on my match that it doesn’t really bother me.

“Honestly, I like when the fans cheer and all this. I think I get pumped. Look, we had a very tough situation years ago when we were playing without fans with the COVID situation, so now, for me, I’m so happy they’re back and I think they’re very important for our sport.”

Grigor Dimitrov

“I think us as tennis players we’re very particular with certain things, and I always say one is the background. For example, let’s say if it’s too bright or if you have, let’s say, big letters, whatever it is, it’s a bit more difficult.

“Also, with the crowd, if you see the crowd moving in the back, it’s very, very tough because we are so focused on the ball. When we see that is moving, automatically your eye is catching that. On the movement part, I’m all for being absolutely still.

“Now, with the sound, there’s not much, I guess, we can do. I think either/or I’m very neutral on that, to be honest. I could play, I don’t know, with music on and all that. Of course, I prefer when everything is, like, a little bit more tame, so to speak, but this is a little bit out of our control.”

Daniil Medvedev

“I think it’s very tough, because there are two ways. So right now, in a way, there are, like, the kind of, I would say, unofficial rule — or actually an official rule, don’t interrupt players before second serve and when they’re ready to serve and during the point. Personally, I like it. Because I think, I don’t know if there are other sports than tennis and golf that have it, but because it’s so technical and, like, I would say every millimeter of a movement you change, the ball is going to go different side.

“So, you know, if someone screams in your ear, your serve, you could double fault. That’s as easy as that. That’s not good. At the other side, if there would be no this rule and it would be allowed all the time, I think we would get used to it. Now what happens is that 95% of matches, tournaments, it’s quiet. And then when suddenly you come to Roland Garros and it’s not, it disturbs you, and it’s a Grand Slam so you get more stress and it’s not easy.

“Yeah, I think playing French in Roland Garros is not easy. That’s for sure. I think a lot of players experience it. I would say that in US Open and Wimbledon is not the same. Australia can be tough. I played Thanasi once there on the small court. It was, whew, brutal. Yeah, I think, you know, it’s a tough question. I think as I just responded, it’s good to have energy between points, but then when you’re ready to serve, it’s okay, let’s finish it and let’s play tennis. Same before first and second serve. And then when there is a changeover, when there is between points, go unleash yourself fully, it’s okay.

“But again, when you’re already bouncing the ball, you want to get ready for the serve, if it would be 10 years we would be playing loud, we would not care. But for the moment it’s not like this so when you get ready for serve, you want to toss the ball, then suddenly ten people continue screaming, the serves are not easy, so for the moment, let’s try to be quiet.”

Conclusion

In conclusion, this year’s crowd has been more volatile and aggressive then seen in previous years which is a big problem for player safety.

However on a whole the crowd is also more passionate and entertaining which makes for a quality product.

As long as the crowd can control their temperament then most of the incidents are nothing but hyperbole and something the players need to get used to in a hostile Parisian environment.

Comments

Steve Flink: The 2024 Italian Open Was Filled with Surprises

Published

2 months agoon

20/05/2024

In sweeping majestically to his sixth career Masters 1000 title along with a second crown at the Italian Open in Rome, Germany’s Sascha Zverev put on one of the most self assured performances of his career to cast aside the Chilean Nicolas Jarry 6-4, 7-5 in the final. By virtue of securing his 22nd career ATP Tour title and his first of 2024, Zverev has moved from No. 5 up to No. 4 in the world. That could be crucial to his cause when he moves on to Roland Garros as the French Open favorite in the eyes of some experts.

Zverev is long overdue to win a major title for the first time in his storied career. Not only has he won those six tournaments at the elite 1000 level, but twice— in 2018 and 2021—he has triumphed at the prestigious, year end ATP Finals reserved solely for the top eight players in the world. This triumph on the red clay of Rome is a serious step forward for the 27-year-old who has demonstrably been as prodigious on clay as he is on hard courts.

Seldom if ever have I seen a more supreme display of serving in a final round skirmish on clay than what Zverev displayed against Jarry on this occasion. He never faced a break point and was not even pushed to deuce. Altogether, Zverev took 44 of his 49 service points across the two sets in his eleven service games. He won 20 of 21 points on his deadly delivery in the first set and 24 of 28 in the second. He poured in 80% of his first serves and managed half a dozen aces and countless service winners. His power, precision and directional deception was extraordinary.

Although the scoreline in this confrontation looks somewhat close, that was not the case at all. Jarry was thoroughly outplayed by Zverev from the backcourt, and despite some stellar serving of his own sporadically, he could not maintain a sufficiently high level. He did manage to win 78% of his first serve points, but Jarry was down at 35% on second serve points won. In the final analysis, this was a final round appointment that was ultimately a showcase for the greatness of Zverev more than anything else. Jarry was too often akin to a spectator at his own match as Zverev clinically took him apart.

Zverev and Jarry arrived in the final contrastingly. The German’s journey to the title round was relatively straightforward. After a first round bye, he handled world No. 70 Aleksandar Vukic. Zverev dismissed the Australian 6-0, 6-4. The No. 3 seed next accounted for Italy’s Luciano Darderi 7-6 (3), 6-2. In the round of 16, Zverev comfortably disposed of Portugal’s Nuno Borges, ousting the world No. 53 by scores of 6-2, 7-5. Perhaps Zverev’s finest match prior to the final was a 6-4, 6-3 quarterfinal dissection of Taylor Fritz, a much improved player on clay this season. Zverev did not face a break point in taking apart the 26-year-old 6-4, 6-3 with almost regal authority from the backcourt.

Only in the penultimate round was Zverev stretched to his limits. Confronting the gifted Alejandro Tabilo of Chile, he was outplayed decidedly in the first set against the left-hander. The second set of their semifinal was on serve all the way, and the outcome was settled in a tie-break. With Tabilo apprehensive because he was on the verge of reaching the most important final of his career, Zverev was locked in. After commencing that sequence with a double fault, Zverev fell behind 0-2 but hardly put a foot out of line thereafter.

He did not miss a first serve after the double fault and his ground game was unerring. Zverev took that tie-break deservedly 7-4, and never looked back, winning 16 of 19 service points, breaking an imploding Tabilo twice, and coming through 1-6, 7-6 (4), 6-2. Zverev displayed considerable poise under pressure late in the second set to move past a man who had produced a startling third round upset of top seeded Novak Djokovic.

As for Jarry, the dynamic Chilean had a first round bye as well, and then advanced 6-2, 7-6 (6) over the Italian Matteo Arnaldi. Taking on another Italian in the third round, Jarry survived an arduous duel with Stefano Napolitano 6-2, 4-6, 6-4. He then cast aside the Frenchman Alexandre Muller 7-5, 6-3.

Around the corner, trouble loomed. Jarry had to fight ferociously to defeat No. 6 seed Stefanos Tsitsipas, who had by then established himself in the eyes of most astute observers as the tournament favorite. Tsitsipas has been revitalized since securing a third crown in Monte Carlo several in April. And in his round of 16 encounter, the Greek competitor had looked nothing less than stupendous in routing the Australian Alex de Minaur 6-1, 6-2.

Unsurprisingly, Tsitsipas seemed in command against Jarry in their stirring quarterfinal. He won the first set and had two big openings in the second. Jarry served at 3-3, 0-40. Tsitsipas missed a lob off the backhand by inches on the first break point before Jarry unleashed an ace followed by a service winner. The Chilean climbed out of that corner and got the hold. Then, at 5-5, Tsitsipas reached double break point at 15-40 but once more he was unable to convert. He got a bad bounce on the first break point that caused him to miss a forehand from mid-court. On the second, Jarry’s forehand down the line was simply too good.

Now serving at 5-6, Tsitsipas had not yet been broken across two sets. One more hold would have taken him into a tie-break and given him a good chance to close the account. But Tsitsipas won only one point in that twelfth game and a determined Jarry sealed the set 7-5.

Nonetheless, Tsitsipas moved out in front 2-1 in the third set, breaking serve in the third game. Jarry broke right back. Later, Tsitsipas served to stay in then match at 4-5 in that final set. He fought off three match points but a bold and unrelenting Jarry came through on the fourth to win 3-6, 7-5, 6-4. That set the stage for a semifinal between Jarry and a surging Tommy Paul, fresh from back to back upset wins over Daniil Medvedev and Hubert Hurkacz.

Jarry and Paul put on a sparkling show. Jarry took the opening set in 42 minutes, gaining the crucial service break for 5-3 and serving it out at 15 with an ace out wide. When Jarry built a 4-2 second set lead, he seemed well on his way to a straight sets triumph. But Paul had broken the big serving Hurkacz no fewer than seven times in the quarters. He is a first rate returner. The American broke back for 4-4 against Jarry and prevailed deservedly in a second set tie-break 7-3 after establishing a 4-0 lead.

Briefly, the momentum was with Paul. But not for long. Jarry saved a break point with an overhead winner at 2-2 in the final set, broke Paul in the next game, and swiftly moved on to 5-2. At 5-3, he served for the match and reached 40-0. But he missed a difficult forehand pass on the first match point and Paul then released a backhand down the line winner and a crosscourt backhand that clipped the baseline and provoked a mistake from Jarry.

The Chilean cracked an ace to garner a fourth match point, only to net a backhand down the line volley that he well could have made. A resolute Paul then advanced to break point but Jarry connected with a potent first serve to set up a forehand winner. The American forged a second break point opportunity but Jarry erased that one with a scorching inside in forehand that was unanswerable. Another ace brought Jarry to match point for the fifth time, and this one went his way as Paul rolled a forehand long. Jarry was victorious 6-3, 6-7 (3), 6-3.

Meanwhile, while all of the attention was ultimately focussed on the two finalists, it was on the first weekend of the tournament that the two dominant Italian Open champions of the past twenty years were both ushered out of the tournament unceremoniously. First, Rafael Nadal, the ten-time champion in Rome, was beaten 6-1, 6-3 in the third round by Hurkacz as he competed in his third clay court tournament since coming back in April at Barcelona.

He had lost his second round match in Barcelona to De Minaur. In his next outing at Madrid, Nadal avenged that loss to the Australian and managed to win three matches altogether before he was blasted off the court by the big serving and explosive groundstrokes of Jiri Lehecka. In Rome, the Spaniard won one match before his contest with Hurkacz. The first two games of that showdown lasted 27 minutes. Nadal had five break points in the opening game and Hurkacz had two in the second game. Neither man broke and so it was 1-1.

A hard fought and long encounter seemed almost inevitable, but the Polish 27-year-old swept five games in a row to take that first set, saving two more break points in the seventh game. He was mixing up his ground game beautifully, hitting high trajectory shots to keep Nadal at bay and off balance, then ripping flat shots to rush the Spaniard into errors. In the second set, Hurkacz broke early and completely outclassed Nadal. He also served him off the court, winning 16 of 17 points on his devastatingly effective delivery. With one more break at the end, Hurkacz surged to a 6-1, 6-3 triumph.

A day later, Djokovic, the six-time Italian Open victor, met Tabilo in his third round contest. Djokovic had played well in his second round meeting against the Frenchman against Corentin Moutet to win 6-3, 6-1. But afterwards, Djokovic was hit in the head by a water bottle while signing autographs. He had the next day off but when he returned to play Tabilo, the Serbian was almost unrecognizable. Beaten 6-2, 6-3, Djokovic never even reached deuce on the Chilean’s serve. On top of that, Djokovic, broken four times in the match, double faulted on break point thrice including at set point down in the first set and when he was behind match point in the second. Tabilo was terrific off the ground and on serve, but Djokovic was listless, lacking in purpose and seemingly disoriented. Some astute observers including Jim Courier thought Djokovic might have suffered a concussion from the freakish water bottle incident, but he did tests back in Serbia which indicated that was not the case.

Now Djokovic has decided to give himself a chance— if all goes according to plan— to potentially play a string of much needed matches at the ATP 250 tournament in Geneva this week. All year long, he has played only 17 matches, winning 12 of those duels. But nine of those contests were at the beginning of the season in Australia. Since then, he has played only eight matches. On the clay, he went to the semifinals in Monte Carlo where he benefitted from four matches, but he skipped Madrid and hoped to find his form again in Rome.

Realizing that losing in the third round there left him not only lacking in match play but not up to par in terms of confidence as well, Djokovic will try to make amends in Geneva. A good showing in that clay court tournament— either winning the tournament or at least making the final—would send the Serbian into Roland Garros feeling much better about his chances to win the world’s premier clay court championship for the third time in four years and the fourth time overall in his career.

How do the other favorites stack up? It is awfully difficult to assess either Carlos Alcaraz or Jannik Sinner. Alcaraz missed Monte Carlo and Barcelona and probably rushed his return in Madrid, losing in the high altitude to Andrey Rublev in the quarterfinals. Then he was forced to miss Rome. He is clearly underprepared. As for Sinner, he played well in Monte Carlo before losing a semifinal to Tsitsipas. He advanced to the quarterfinals of Madrid but defaulted against Felix Auger-Aliassime with a hip injury.

Will Alcaraz and Sinner be back at full force in Paris? I have my doubts, but the fact remains that Sinner has been the best player in the world this year, capturing his first major in Melbourne at the Australian Open, adding titles in Rotterdam and Miami, and winning 28 of 30 matches over the course of the season. Alcaraz broke out of a long slump to defend his title at Indian Wells, but missing almost all of the clay court circuit en route to Rome has surely disrupted his rhythm.

I would make Zverev the slight favorite to win his first Grand Slam tournament at Roland Garros. If Djokovic can turn things around this week and rekindle his game, there is no reason he can’t succeed at Roland Garros again. I make him the second favorite. Out of respect for Alcaraz’s innate talent and unmistakable clay court comfort, I see him as the third most likely to succeed with Sinner close behind him. But that is assuming they are fit to play and fully ready to go.

Tsitsipas and Casper Ruud must be taken seriously as candidates for the title in Paris. Tsitsipas upended Medvedev and Zverev in 2021 to reach the Roland Garros final, and then found himself up two sets to love up against Djokovic before losing that hard fought battle in five sets. Ruud has been to the last two French Open finals, bowing against Nadal in 2022 and Djokovic a year ago. They started this clay court season magnificently, with Tsitsipas defeating Ruud in the Monte Carlo final and Ruud reversing that result in the final of Barcelona. Both men figure to be in the thick of things this time around at Roland Garros.

Where does Nadal fit into this picture? He will surely be more inspired at his home away from home than he was in his three other clay court tournaments leading up to Roland Garros, but it will take a monumental effort for the 14-time French Open victor to rule again this time around. With a decent draw, he could get to the round of 16 or perhaps the quarterfinals, but even that will be a hard task for him after all he has endured physically the last couple of years. Nadal turns 38 on June 3. If he somehow prevails once more in Paris, it would be the single most astonishing achievement of his sterling career.

The battle for clay court supremacy at Roland Garros will be fierce. The leading contenders will be highly motivated to find success. The defending champion will be in full pursuit of a 25th Grand Slam title. Inevitably, some gifted players will be ready to emerge, and others will be determined to reemerge. I am very much looking forward to watching it all unfold and discovering who will be the last man standing at the clay court capital of the world.

NOTE: All photos via Francesca Micheli/Ubitennis

Paris Olympics Daily Preview: Osaka Plays Kerber, Nadal Teams with Alcaraz

Tennis At The 2024 Paris Olympics: Five Things You Need To Know

Rafael Nadal’s Double Olympic Bid In Doubt, Confirms Coach Moya

Matteo Berrettini extends his winning streak to eight consecutive matches to reach the semifinal in Kitzbuehl

Novak Djokovic’s Potential Second Round Clash With Rafael Nadal Headlines Olympics Draw

Wimbledon Says No To Euros, No To Sunday Starts But Yes To An Andy Murray Statue

Wimbledon: Frances Tiafoe – ‘I Was Losing To Clowns And Took The Game For Granted’

Andrey Rublev Explains On-Court Outburst Following Wimbledon Exit

EXCLUSIVE: Sumit Nagal Brings Indian Tennis To The Main Stage But He Has Concerns About The Future

(VIDEO) Jannik Sinner Set To Renew Rivalry With Defending Champion Alcaraz, Djokovic Ready To Play

(VIDEO) What Is Wrong With Jannik Sinner?

(VIDEO) Ubaldo And Steve Flink – “Djokovic Was Too Flat, Alcaraz Triumphs Yet Again At Wimbledon”

(VIDEO) Steve Flink, Ubaldo On The Wimbledon Women’s Final: ‘The Better Player Won But Did Inexperience Play A Part?’

(VIDEO) Ubaldo And Steve: “Paolini’s Resilience Earns Her Another Stunning Grand Slam Final”

(VIDEO) Amazing Lorenzo Musetti Sets Up Djokovic Showdown At Wimbledon

Trending

-

Hot Topics3 days ago

Hot Topics3 days agoNo Olympic Village Stay For Novak Djokovic In Paris, Says Delegation

-

Latest news3 days ago

Latest news3 days agoWorld No.634 Laura Samson Reaches First WTA Quarter-Final At 16

-

Hot Topics2 days ago

Hot Topics2 days ago(VIDEO) What Is Wrong With Jannik Sinner?

-

Hot Topics3 days ago

Hot Topics3 days agoFive Talking Points Ahead Of The 2024 Olympic Men’s Tennis Tournament

-

Focus2 days ago

Focus2 days agoJannik Sinner Withdraws From Olympics Due To Tonsillitis

-

Focus2 days ago

Focus2 days agoMatteo Berrettini battles past Alejandro Tabilo to reach the quarter final in Kitzbuehl

-

Focus2 days ago

Focus2 days agoCoco Gauff ‘Proud’ Of Being Named Olympic Flagbearer alongside Lebron James

-

Hot Topics2 days ago

Hot Topics2 days agoAndy Murray At Peace With Retirement Decision Ahead Of Olympic Farewell