At twenty-four, Alexander “Sascha” Zverev is clearly among the best five players in the world, having achieved in 2017 his best ranking of world N.3 and having recently won the gold medal at the Olympics in Tokyo. This would be enough, perhaps, to highlight the talent of the young German of Russian origins, but there is much more to it: he can attack from the baseline with great ease both from the forehand and the backhand sides, and combines these skills with one of the most powerful serves on tour. After his first appearance in an ATP tournament (he won his first match in Hamburg in 2014 as a wild card), many foresaw a bright future for him.

Instead, in spite of 17 career titles, Zverev has not yet been able to win a Major, the Litmus test for every great champion. Even in the last edition of Wimbledon, Zverev succumbed to underdog Félix Auger-Aliassime in a five-setter.

Let’s look for an explanation within the data, particularly those that refer to the 79 singles matches he has played so far in Melbourne, Paris, London and New York, in order to try to better understand the causes of this discordant note in what is already a great career nonetheless.

RESUMÉ

Before focusing on Grand Slam matches, it is worth mentioning that the German number one has already won five Masters 1000 titles: the first on clay in Rome in 2017, defeating Djokovic in the final in straight sets; the same year, he won the tournament in Montrèal (on hardcourts), this time beating Federer. Then he won in Madrid twice, in 2018 and 2021 on clay, beating Thiem in 2018 and Berrettini in 2021, before recently winning in Cincinnati against Rublev. Not to be forgotten are the most precious jewels of Zverev’s collection, namely the triumph of the ATP Finals 2018 – once again defeating Djokovic after having eliminated Federer in the semis – plus the aforementioned Olympic gold medal, beating Djokovic once more before dispatching Khachanov in the final.

It was precisely the win at the O2 Arena three years ago that seemed to have definitively propelled Sascha to the pinnacle of world tennis, not only because of the wins per se, but also for the extraordinary quality of play he expressed in all areas of the court. Instead, something seemed to stop working.

In 2019, Zverev reached “only” three finals: in Geneva, in Acapulco, and at the Masters 1000 tournament in Shanghai. However, only in Switzerland he could get to the title (in a third-set tiebreaker against Nicolás Jarry), while he was soundly defeated by Kyrgios in Acapulco and by Medvedev – in steamroller mode – in Shanghai.

In 2020, a season marked by the pandemic, Zverev seemed close to a big break. He first reached the semifinals at the Australian Open (his first at a Major) and then reached the final of a Grand Slam tournament for the first (and currently, only) time at the US Open. In both circumstances, he faced his good friend (and rival) Dominic Thiem. The fast surface should have, on paper, given an edge to Zverev, who in fact won the opening two sets in Flushing Meadows with a score of 6-2 6-4. At that point, once again, the tune changed: Thiem found new energies, while Zverev struggled. After tying the score, it was the Austrian who won the decisive tiebreaker, denying Zverev the trophy.

The 2021 season seems to fit into the same pattern: Zverev has already won four finals including two at Masters 1000 events, he is fourth in the Race and won gold in Tokyo, and yet he couldn’t go past the quarter finals in Australia, the semifinals in Paris (defeated by Tsitsipas in five sets), and the aforementioned 4th round at Wimbledon. So, a great regularity at high levels but with no real peak (compared to the level of play that he is able to express). Let’s now take a closer look at the data to try to better understand this dynamic.

OVERVIEW

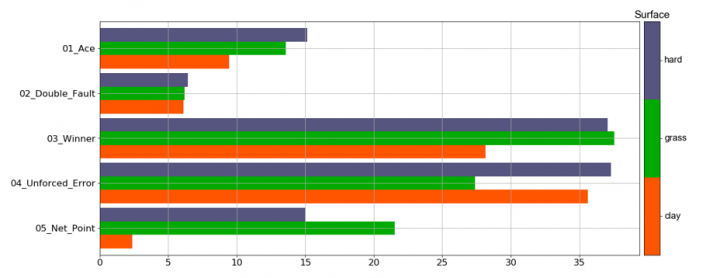

Before delving into the analysis in search of winning and losing patterns, an overview will be presented, framing Zverev’s style of play with a series of statistics, the average values of which are shown in Figure 1, separately by surface.

It can be observed how both the average number of aces (in particular on fast courts) and that of double faults is quite high, proving that the serve is, in a way, both a blessing and a curse for the German player. He gets many points from it but, at the same time, it is that very stroke which sometimes puts him in danger, especially in clutch moments.

Comparing different surfaces, a good balance can be observed: of course the number of winners is bigger on hard and grass, due to the specificities of these surfaces, and the difference in the number of net points is also easy to understand (albeit quite marked): almost absent on clay, definitely more frequent on hard, and even more on grass. A second set of statistics, shown in Figure 2, can help us get an even more precise idea:

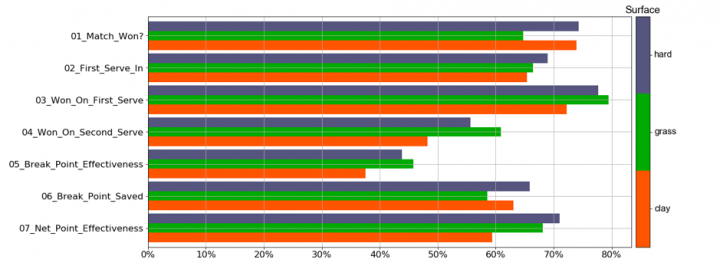

We note, in particular, a significant decrease in the percentage of points won with the second serve, compared to the percentage of points won with the first serve. On all surfaces, Zverev wins more than 70% of points with the first serve, while only on grass he exceeds 60% with the second, falling under 50% on clay.

It is only natural to attribute this difference to psychological factors too, given that in his first 1000 final, on the Rome clay in 2017, in a best-of-three tournament against the best returner on tour (and probably the greatest returner of all-time, Novak Djokovic), Zverev managed to win 69.2% of points on his second serve. The underdog role he played that day perhaps allowed him to play with less pressure and to showcase his qualities.

To be noted is a good effectiveness for Zverev at the net, particularly on hardcourts, where he wins over 70% of such points. Let’s now try to deepen the analysis, looking for patterns related to a Zverev win or defeat in a best-of-five match.

MOST SIGNIFICANT PATTERNS, THE KEY ELEMENTS OF ZVEREV’S GAME

So far, we have focused on Zverev’s game one aspect at a time. In this section, with the help of technology, we will consider more aspects simultaneously in order to develop a multivariate analysis. In particular, we will try to find out which of the various match statistics (which represent our input variables) are decisive, and how so, with respect to victory or defeat (which represent our output variables).

For greater clarity, we will ensure that the classification algorithm used will automatically return – based on the available variables – a model consisting of a set of rules which represent the statistically most significant patterns that lead the German to winning or to losing. Below, we illustrate the three most significant rules calculated as follows:

1 – “If Zverev wins at least 4.7% more points than his opponent with his first serve and hits fewer than 15 double faults, then he wins the match.” This pattern is quite general but extremely precise: it occurs in more than half of the matches won by Zverev in Grand Slam tournaments (to be precise, in 56%, corresponding to 38 matches) and in none of his 22 losses.

2 – “If Zverev hits at least 3.2 more winners than his opponent per set, then he wins the match.” This pattern is extremely precise: it occurred in 18 cases and Zverev won every time.

3 – “If Zverev does not win at least 2.1% more points than his opponent with his first serve, if he hits fewer than 43 winners, and if he amasses more than 27 unforced errors, then he loses the match.” This pattern is even more specific but, once more, there are no exceptions: it occurred six times and Zverev lost in all circumstances.

The more a stat appears as a relevant condition within these patterns, the more we can define it as a key element of Zverev’s game. We will therefore be able, on the basis of the data, to draw up a feature ranking of the various aspects of his game, distinguishing those that, to a greater extent, alone or in combination with others, prove to be decisive.

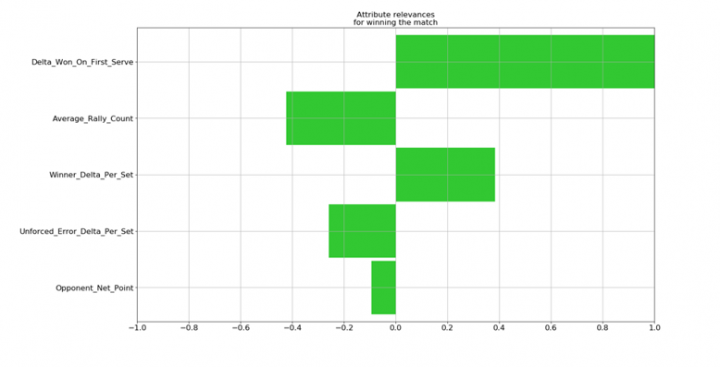

As can be seen in Figure 3, the most important element for Zverev turns out to be the difference in performance compared to the opponent in terms of the points won with his first serve. Of course, as this difference increases, the probability of victory also increases, and that is why the corresponding bar of the graph (the top one) points to the right, indicating a direct correlation. On the contrary, the second bar indicates an inverse correlation with respect to the average number of shots per rally: in other words, the shorter the rallies, the likelier Zverev is to win the match. Examining the other three bars which constitute the feature ranking, we can identify, as other items of interest, the difference with the opponent in terms of the number of winners (direct correlation) and unforced errors (inverse correlation) and, albeit more weakly, in terms of the number of net points played by the opponent (inverse correlation).

Trying to interpret these results, we are led to deduce that, from a more general perspective, the key element for Zverev may be his level of initiative. In other words, if the German looks to win many quick points, shortening the rally and not offering to his opponent the opportunity to get to the net too often, as the data also tells us, he has a very good chance of winning the match. Of course, unforced errors also have a weight: this attitude must not become too wasteful in terms of points gifted to the opponent.

Trying to summarize further and to move from data analysis to tactical choices, one could perhaps venture a piece of advice to Zverev, actually often reiterated by many experts: he should try to play as close as possible to the baseline. In fact, it is from that position that he manages to be aggressive without forcing too much and without letting himself be trapped in a thick web of long rallies. Who knows whether Sascha, mindful of his loss against Auger-Aliassime at Wimbledon, will decide to give this tactic a try, perhaps as early as the upcoming US Open.

Article by Damiano Verda; translated by Alessandro Valentini; edited by Tommaso Villa