Sportsmen have always had passionate and devoted fans, but becoming more visible implies the development of one’s own personal branding – but what is it? It is the practice of actively positioning oneself in the market and building a “valuable narrative”, creating a brand, a mark or a “mnemonic” to support this message, association, expectation and/or “faith” in the mind of a “consumer” (or enthusiast, team, sponsor, etc).

The term “personal branding” was coined by Tom Peters, a business management expert, in the late 1990s, in his essay “The Brand Called You”, which examines the role of marketing in creating a distinctive image in the American corporate world. Although that essay is over 20 years old, its contents are even more relevant in today’s hyper-saturated, hyper-competitive and hyper-connected world, in which differentiation strategies are becoming increasingly complex. The sports market is in fact characterised by a high degree of complexity as it encompasses a multitude of actors, each of them with certain characteristics and interests.

Following the categorization of sports marketing, personal branding can be understood as being incorporated into the marketing of individual athletes, and as a branch of sports marketing.

Initially, sports marketing exclusively pertained product placement and product sales. Only towards the end of the 1970s did the use of sports as a marketing tool really begin to catch the collective corporate imagination. However, a distinction must be made between sports sponsorship – which mainly concerns brand awareness – and sports marketing, which focuses on the creation of sponsorship contracts. Personal branding is about creating a connection between the sports icon and the brand, then communicating it to the consumer, trying to find as many points in common between the company’s history and that of the icon in order to create a “narrative” that has to be understandable and appreciated by the consumer. The increasing popularity of sports and the resulting media coverage meant that the best players were able to capture the hearts and minds of the public, thus starting to transcend their own discipline. Interestingly, companies don’t just look at investment return in money terms, their primary aim being to create emotional bonds with consumers. Sports marketing is now based on creating passion for the consumer and gaining their hearts and minds, an outcome that advertising campaigns alone are not always able to achieve.

THE NIKE-JORDAN PARTNERSHIP MARKS A WATERSHED MOMENT

An experience that has certainly changed sports marketing has involved basketball icon Michael Jordan, who, signed to the sports giant Nike, has become so important that it is felt by consumers as being a different branch, separated from the Oregon company. We often hear “these shoes are Jordans”, or “this shirt is a Jordan”, completely omitting the fact that the full brand is “Nike Jordan”. On this account, at the end of 1997 the Portland company realised that the “Jordan” brand was so strong it could become a sub-brand of Nike, and that was how “The Jordan Brand” was born. To celebrate this, the first AIR model was released: the “AIR Jordan XIII”. From then on, Jordan shoes no longer sported Nike’s swoosh but only the “Jumpman” logo.

Back to the world of tennis and some years earlier, the first successful brands were those of ex-players such as Lacoste, Perry and Tacchini, who gave life to important companies selling sports clothing and accessories, entrepreneurial initiatives that leveraged specific marketing tools for sports equipment and clothing.

All these entrepreneurial cases have one thing in common: the establishment of the production and marketing companies took place after the specific tennis player had ended his sports career, exploiting – in the case of Lacoste and Perry – a fame already acquired, but limited only to enthusiasts of the game. These brands, although no longer dominant, are still present on the market today. Lacoste can still boast the sponsorship of three WTA and five ATP players in the Top 50 of their respective rankings, including recent Australian Open finalists Djokovic and Medvedev. Fred Perry resurfaced in 2009 as a sponsor of Andy Murray’s, and has been organising a major youth tournament in the UK since 2019. Sergio Tacchini has recently reappeared as a technical sponsor, after having been the dominating force in tennis merchandising during the 1980s – as for Lacoste and Fred Perry, we are talking about brands which are strongly linked to their national context.

THE CURRENT SITUATION IN TENNIS ENDORSEMENTS

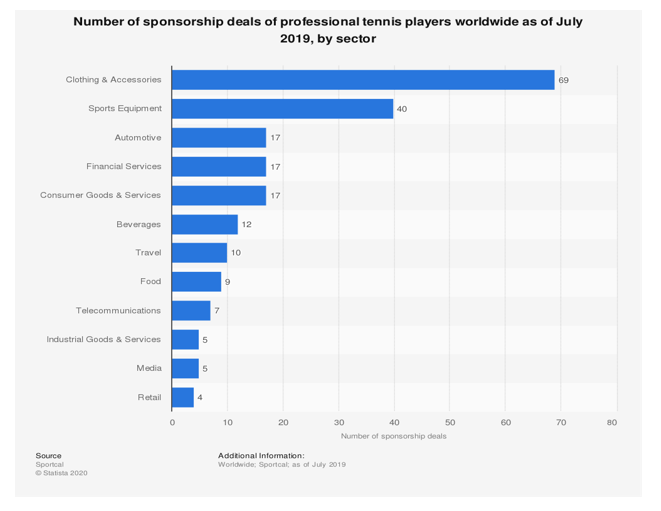

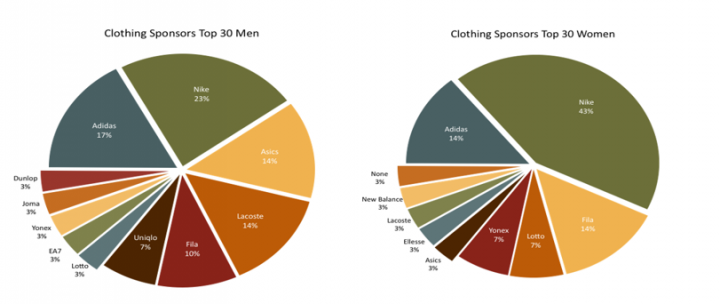

Even today, the largest number of sponsorships of a tennis player concerns sports clothing and accessories:

The distribution of the brands has changed, however, as can be seen when looking at the Top 30 on both the WTA and ATP tours.

So, what has changed? The context variables (external and internal) are simply different, and there is a greater awareness on the part of successful athletes about the value of their image. The external environment is made of factors apparently furthest away from the endorsing company, including technologies, demographics and social trends, economic issues, politics, laws, concepts of environmental sustainability. The internal environment consists in variables such as: resources, skills, the ability to provide services, customer-oriented culture, performance of departments, suppliers and outsourcing, sponsorships, marketing channels (sales outlets, financial companies, communication) and the role of the general public. These variables converge in the SWOT matrix (Strength-Weakness-Opportunities-Threats), which in turn flows into the marketing plans, allowing experts to mitigate risks, improve process efficiency and the decisional effectiveness of the marketing activities.

Advertising and marketing strategies have evolved over the past 30 years, and no tactics that companies and organisations use to get the consumers’ attention has undergone more transformations than sports endorsing. In the past decades, advertising executives could buy large amounts of advertising space on television networks and “bomb” viewers with ads. The formula was simple: whoever spent the most, won. Today, however, as consumers watch less television and the selection of viewing options has increased exponentially, brands are forced to diversify and invest money to find new ways to engage potential customers. It took years of low incomes to realise that simply paying for your logo to appear alongside that of a professional sports team, buying TV commercials or advertising in stadiums during matches no longer provided the same profit it used to.

So, if the notion of getting a high return on investment from traditional advertising campaigns is almost dead, how can companies achieve success for their brands in terms of consumers’ appreciation? They need to leverage customer passions and promote brand relationships: collaborations today aim to improve the experience of the consumer or enthusiast and are based on building relevant connection points between the customer, the athlete and the corporate brand he/she represents.

Today we are witnessing a proliferation of personal brands, such as those listed below. Normally they are sub-brands, with some exceptions like that of Roger Federer, able to buy back his “RF” logo after a long legal battle with Nike. Self-referencing brands are just the tip of an iceberg in a brand-building strategy to obtain a long and successful career outside of sports. Even after an athlete’s sporting career is over, many carry their personal brand with them, just like Michael Jordan.

STRATEGIES

The distance between sports fans and champions has diminished, as social media and the web contribute to create emotional involvement and loyalty, together with traditional channels. Some general rules can be identified in the construction of a strong brand identity:

- Create coherence between the personality and the values of the athlete and his/her personal brand. It’s important to create a personal story that puts the athlete under an authentic light, which is not too far from his true character. There is no need to create a discrepancy between your real story and the image you intend to communicate externally. So, you must always check that the personal narrative is aligned with the core of the person.

- Promotion of philanthropic causes. Showing of the selflessness of sportsmen is manifested in causes where there are strong inequalities. Athletes who sincerely try to help solve even a small problem will not only be invested with the merits of positivity in solving the problem but will also benefit from a significant impact on their personal brand’s value and positioning.

- Control of one’s own personal branding in detail. Keeping control of even the smallest detail makes it possible to think of forming really interesting PR strategies for brand development that can target narrow segments of professionals, whilst ordinary fans may not even be aware of it.

- Select appropriate tools apt to interact with each of the important segments of the target audience. In most cases, when building athletes’ brands, one opts to use only a standard set of channels and tools. Today it is enough to take your personal brand to the top, as in reality no one is trying to achieve more in the sport, but in the near future this will not be enough anymore, given the enormous competitive pressures. Therefore, it is necessary to invest 80% more to obtain a substantial 100%. The world around us is developing fast, and athletes have to work hard to stay in the conversation.

- Each action must be framed within the context of the positioning of the personal brand. An athlete who has global visibility must pay attention to all personal actions, as this is relevant to the positioning of his brand, built around his personality and individual beliefs.

THE PERSONAL BRANDS OF PROFESSIONAL TENNIS PLAYERS

In order to find the aforementioned characteristics, a small empirical research was conducted on the personal sites and philanthropic initiatives of the so called “Fab Four”. Their sales in relation to their foundations or academies are summarized below:

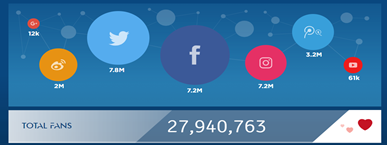

Although Sir Andrew Barron Murray does not have a foundation or a clothing collection with his personal brand, he is involved in several philanthropic initiatives. Both Murray and Djokovic have personal pages on Sina Weibo, a Chinese microblogging site, which is in fact a hybrid of Twitter and Facebook, and is one of the most popular sites in China. Djokovic’s numerical approach to social media is also very original, given that his site has a counter that adds up all his fans interactions scattered across the various social media channels, reporting the latest tweets.

Nadal’s conception of the relationship with his fans is instead more traditional: it includes a sort of virtual bulletin board with many pictures taken in the company of his devoted followers. Federer moves along similar lines, using the classic channels, namely Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, with a gallery of historical photos of the matches played in his professional seasons. Moreover, the fact that other tennis players such as Stan Wawrinka, Stefanos Tsitsipas, Marco Cecchinato, and more recently Jannik Sinner have chosen to create their personal brands, with the aim of improving their communication and marketing strategy, needs also to be remarked.

CONCLUSIONS

Why is personal branding becoming more and more common? If we look at those who already have a brand, the answer is closely linked to the business of professional sport, and is simply the ability of an athlete to generate a return from their image. Analysing the concept with a critical spirit and keeping in mind the goal of maximising incomes for a sportsman during his or her short career, there are three basic reasons for building a “personal sports brand”:

- Effectiveness

- Relevance of their Image, which triggers the Fear of losing it

- Level of importance, which will change throughout a professional athlete’s career span.

In the beginning or mid-career, a personal brand or a support logo are forms of efficient involvement of sponsoring companies, because they indicate the values that an athlete possesses and that a brand could exploit via an endorsement. As the athlete heads towards the twilight of his professional career, the motivation becomes fear and relevance or, more precisely, the fear of not being relevant anymore. The skills of a professional athlete will naturally establish a certain positioning in the minds of the stakeholders, but an active cure of a market position derived from this ability is a strategic undertaking that requires not only a change in the mentality of an individual, but, above all, a shift in managerial culture to encourage athletes to think long-term and beyond the immediacy of their physical ability.

Cultivating the mental and physical well-being of a professional sportsman is the job of a manager or a coach, but when it comes to thinking ahead, many athletes are woefully unprepared. A retired athlete will come from a world where everything revolves around him and will land on another where he quickly loses the spotlight.

Therefore, strong brand recognition will generate opportunities for athletes throughout their careers, and once they stop playing the game, the effectiveness with which they have defined, positioned and built their image and values will have an impact on their future after tennis. If they postpone the aforementioned definition of their brand for too long, the lack of relevance they fear so much will undermine the value they offer to society, in which standing out requires far more than a logo.

Article by Andrea Canella; translated by Alessandro Valentini; edited by Tommaso Villa