Topspin groundstrokes are the ever-present feature of contemporary tennis. As it goes, the widening of racquets’ sweet spots (starting in the early 1980s) allowed for a greater net clearance, lowering the rate of baseline errors without losing girth on the shot, quite the opposite. In some kind of arms race, grips and swings have developed as well (as highlighted by this New York Times piece), increasing the role of topspin even more, to the point that “flat shot” is a mere figure of speech in today’s tennis, as almost every shot generates rotation, especially on the forehand side.

At the same time, however, data needs to be relativized. While it’s true that all players put topspin on their shots, at the same time some put more than others, de facto flattening the less spinny ones in the perception of the opponent – a playing style is necessarily tied to the way a foe relates to it.

A compelling analysis can thus be to compare the numbers of each player, albeit in the limited setting of the Masters 1000 and the two Finals, the NextGen and the Master, which are the only events for which Tennis TV provides public information.

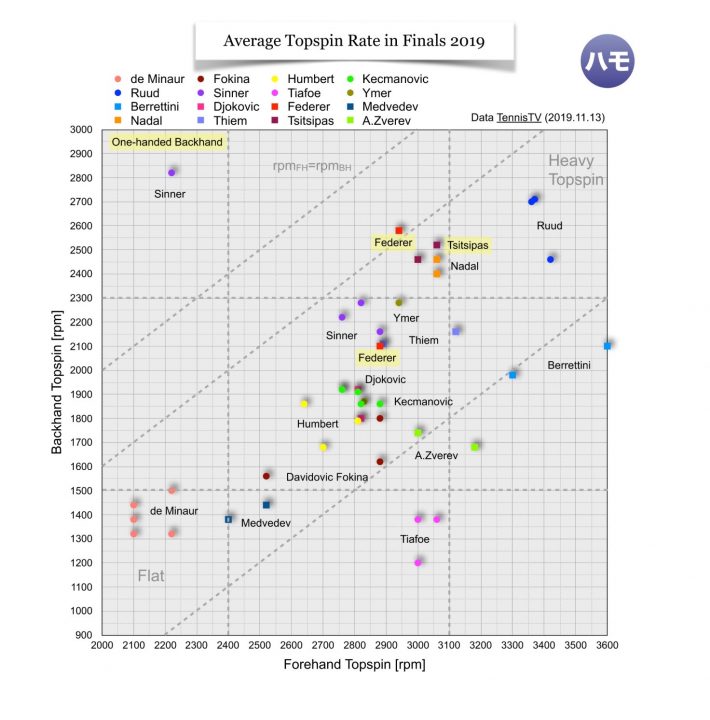

As a matter of fact, the latter two tournaments have been an object of study for the analyst 禮 (his handle is “Vestige du jour,” a likely nod to Kazuo Ishoguro, a fellow Japanese expatriate), a Twitter user who lives in Paris and who has collected the available topspin data for the 16 players who competed in the year-end bouts. Here’s the graphics, with the caveat that he used RPM, Round Per Minute, as a measure, instead of Tennis TV’s RPS, Rounds Per Second, probably to emphasise the differences between the various samples:

Clearly, these are very limited samples, and should therefore be taken with a grain of salt (each player played a maximum of five matches), but a few inferences can be made, three of which appear to be more interesting than others.

HOMOLOGATION – The first, and most relevant, pertains the proportionality vis-à-vis the data on almost every player’s groundstrokes. it can be noticed that most rates are in the central lane of the diagram, with a ratio of about 60-65% between the rotation of the backhand and that of the forehand, barring unique styles like Tiafoe’s, whose forehand’s rate is over 3000 RPM, more than twice as much as his backhand (an even starker antinomy would emerge from the analysis of Britain’s Cameron Norrie), or single instances like Sinner’s route of Ymer (he went over 2800 with his backhand while flattening his forehand to 2200, but that match ended with a 4-0 4-2 4-1 score, far too lopsided to carry meaningful insights).

Specifically, most players have an average between 2700 and 3000 RPM on the forehand, and between 1800 and 2300 RPM on the backhand, respectively – this category features Djokovic, one Federer match, one Zverev match, Humbert, Kecmanovic, Sinner, Davidovich Fokina, and Ymer, pretty much half of the involved players, most of whom are youngsters, giving interesting indications as for the direction the game is moving towards.

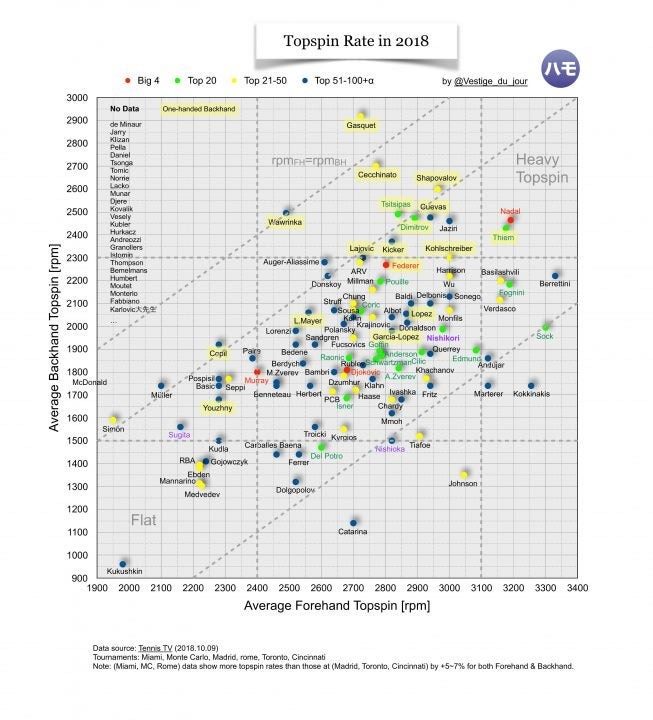

This percentage of homologation is confirmed by another chart prepared by our numbers-crunching friend, which extends the study to six Masters 1000 events from the 2018 season (Miami, Monte Carlo, Madrid, Roma, Canada, Cincinnati):

An interesting corollary emerges when looking at the low reported average of Alex De Minaur and Daniil Medvedev, two players with a few shared quirks, such as their eastern grip which leads them to hit the ball with no exaggerated pronation and supination of the forearm, inherently generating less spin. Their semi-flat style extends to the backhand too, though, and this combo has them labeled as counterpunchers, given their penchant for using their opponent’s speed to generate their their own on both sides.

What seems relevants with regards to the two of them (and the same can be said for Murray, Simon, Mannarino, Bautista Agut, and especially Kukushkin) is that their reputation and imagery as reactive players is a great example of how the classic dichotomies of our sport have shifted, particularly with the way we look at offensive and defensive players, creating a chasm between tennis’s signifiers and signifieds. Until 15-20 years ago, attacking players hit hard and flat on fast surfaces, while grinders overcharged with topspin on slower turfs, whereas now most aggressive players rely on condor-like backswings and therefore prefer the clay and slow hardcourts, as opposed to the aforementioned counterpunchers who find their natural habitat indoors (thanks to the clean shots they can get) and on quick ground – Medvedev’s performance at the ATP Finals notwithstanding, since he’d been out of gas for weeks. In our view, this is the most interesting subject in contemporary tennis, and even though there isn’t much room in this piece to elaborate on its etiology (from physical changes to new tools to different surfaces), which should definitely be tackled in future, and it’s very meaningful nonetheless to highlight how the numbers confirm this transfiguration.

EVOLUTION – The second point revolves around the admirable adaptation that clay-bred champions (e.g. Nadal and Thiem, it’d be insulting to call them specialists) have undergone in order find success on the indoor Green Set of the O2 Arena.

Their versatility emerges when looking at the second chart above. As can be noticed, their topspin rate is a lot higher on clay and outdoors. This is due to the fact that greater humidity lowers the bounce indoors, making tospin shots anodyne and punishing players who stand far from the baseline, inherently forcing them to go for flatter shots (or better, less spinny), more advanced stances (something that in turn forces them to shorten the backwings), and more vertical ball-placements – this datum is rendered even more apodictic by the second chart’s footnote, reporting a 5-7 %increase in tospin rates in the three slower events, Miami (tropical hardcourt, much more humid than Madrid’s MASL-caused rarefied air), Monte Carlo, and Rome.

The contrasti s particularly stark for the Austrian, and it’s a clear symtpom of his incredible technical strides under the aegis of Nicolas Massù, especially regarding his anticipated backhand down the line (a great net play aide) e more generally his on-court positioning, far more advanced than it used to be.

Flipping this line of reasoning, on the other hand, it can be inferred that players with similar rates who have disappointed in these two events (e.g. Ruud and Berrettini, who finished with one win and five losses between the two of them) still haven’t completed their game to the point of being able to skin-change in less friendly conditions. Ruud, in particular, spins mightily from both sides (something that’s helping him in South America), and is the only player who regularly clocks at over 2400 RPM with a two-handed backhand, excluding Sinner’s one-spin-wonder.

LIMITATION? – One more contemporary axiom-disproving stat, at least among fans, is the one pertaining the topspin rate of one-handed backhands, which are purportedly without a future in their being less assertive than their paired evolution. This is a false myth though, a straw-man argument: as can be seen, the three one-handed backhands featured at the ATP Finals (Federer, Tsitsipas, Thiem) have always hit above the 2100 mark, resulting heavier than almost all of their rivals’ ones, and the truth becomes undeniable when looking at the second chart, in which all backhands averaging over 2300 RPM (except for Jaziri’s and Nadal’s) are one-handers.

The bane of such shots doesn’t abide in its abrasiveness (a longer lever generates more spin and more speed as opposed to the closer-to-the-body contact point of a two-hander) as much as in its practical use: as a matter of fact, the same distance from the contact point makes it a lot more problematic on high balls (just think of the long years of strife that Federer has endured on the left side against Nadal). What’s more, the necessity to execute a wide backswing and to hit it in a closed stance limit the shot on fast surfaces, both in the rally and in returning – it could be said that its Achilles’ heel actually stems from its very firepower, which hinders versatility in its elaborateness, especially for those who don’t possess a good slice backhand.

Some might object: what about three out of four semi-finalists at the ATP Finals being one-handers, though, without considering the many others who have performed well during the 2019 indoor season, such as Shapovalov, Dimitrov, and Wawrinka. That is unquestionably true, but a few things need to be clarified: firstly, some of these players (Federer, Dimitrov, Shapo) possess such arm-speed that they can adapt easily to such conditions, actually thriving in them, due to the effectiveness of the slice backhand of Federer and of his epigone; secondly, Thiem and Tsitsipas have had to change their game a lot to accommodate the surface switch and to succeed, learning how to hit earlier and flatter in order not to lose ground – quick demonstration, consider how many more one-handers are doing better on clay than they are on grass, and that’s precisely because bouncy slowy clay allows to hit hard from afar, whereas SW19’s lawns are unpalatable for every one-hander whose name isn’t Roger, in another flip of long-held convictions.

We’d like to end on an idea, which is that analytics help us mediate between our own prejudices and the reality of phenomena, providing us with objective considerations that could seem counter-intuitive at first sight. The dyad involving semi-flat counterpunchers and one-handed backhands (especially in relation to the surfaces on which they perform best) is the perfect representation of such concept. While it’s true that the topspin rate is just one side of the coin, it’s also true that this is exactly the kind of number that could have an impact in the upbringing of new talents, especially in the wake of a game that is becoming more and more rooted in quick points (0-4 shots) and on powerful solutions, and this evolution might widen the gap between those punchers and counter-punchers. Is this the direction the game’s going towards?